Time Series Analysis: Advanced Big Data Processing Methods

Master Time Series Analysis! Explore advanced big data processing methods for high-volume, real-time data. Learn scalable algorithms to transform your analytics.

In the rapidly evolving landscape of data science, time series data has emerged as an indispensable asset, driving critical insights across virtually every industry. From predicting stock market fluctuations and monitoring patient vital signs to optimizing IoT device performance and understanding consumer behavior, the ability to analyze data points indexed by time is paramount. However, the sheer volume, velocity, and unique characteristics of this temporal data present formidable challenges for traditional data warehousing solutions. Standard relational databases, often optimized for transactional processing or static analytical queries, struggle to efficiently store, process, and retrieve time-stamped information at the scale required by modern applications. This often leads to performance bottlenecks, prohibitive storage costs, and a significant impediment to timely, data-driven decision-making. The demand for sophisticated analytical capabilities, particularly for forecasting, anomaly detection, and trend analysis, necessitates a radical rethinking of how we design, implement, and manage our data warehousing infrastructure. This article delves into the cutting-edge of time series analysis within the context of advanced data warehousing methods, exploring the specialized architectures, innovative data models, and optimization strategies essential for building robust, scalable, and high-performance systems capable of harnessing the full power of temporal data. We will navigate the complexities of temporal data warehousing, examine techniques for time series data storage optimization, and provide a comprehensive guide to effective data warehouse design for time series, ultimately unveiling the principles of a resilient big data time series architecture fit for the challenges and opportunities of 2024 and beyond.

The digital age is characterized by an explosion of data, much of which inherently possesses a temporal component. Every interaction, every sensor reading, every transaction leaves a time-stamped trail, forming a vast and continuous stream of time series data. Understanding the nature and significance of this data is the first step towards building effective warehousing solutions.

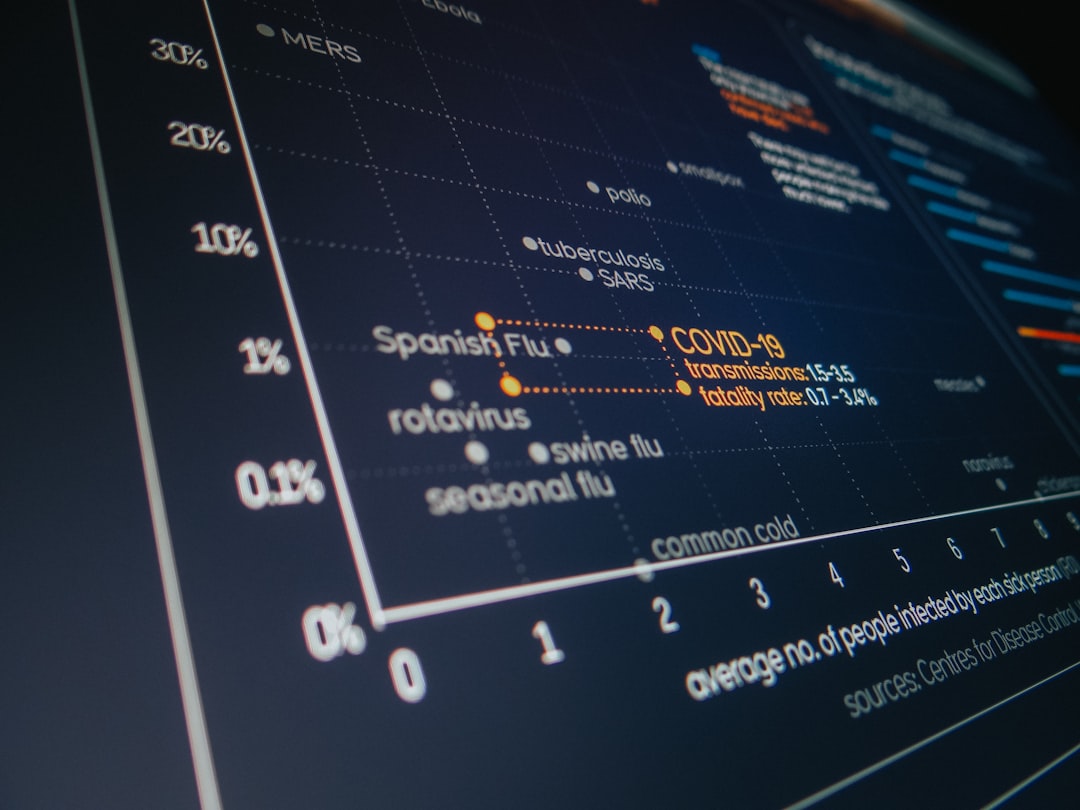

Time series data is everywhere. In finance, it includes stock prices, trading volumes, and economic indicators. In healthcare, it encompasses patient vital signs, treatment histories, and epidemic progression. Industrial IoT devices generate continuous streams of sensor data from machinery, monitoring temperature, pressure, vibration, and energy consumption. E-commerce platforms track website clicks, purchase histories, and user session durations. Telecommunications networks log call data records and network traffic patterns. Even environmental monitoring systems collect atmospheric data, water levels, and seismic activity over time. The inherent value of time series data lies in its ability to reveal patterns, trends, seasonality, and anomalies that are invisible in static datasets. This allows businesses and researchers to predict future outcomes, diagnose root causes of problems, optimize processes, and make proactive decisions.

For instance, in predictive maintenance, analyzing vibration sensor data from a machine over time can help forecast equipment failure before it occurs, significantly reducing downtime and maintenance costs. In retail, understanding the temporal patterns of sales can optimize inventory management and staffing levels. The analytical insights derived from robust time series analysis are critical for competitive advantage and operational excellence, making efficient storage and retrieval of this data a top priority.

Time series data exhibits several unique characteristics that differentiate it from other data types and pose specific challenges for traditional data warehousing. Firstly, it is inherently sequential; the order of data points is crucial, and each point is typically associated with a timestamp. This makes operations like aggregation over time windows, resampling, and interpolation fundamental. Secondly, time series data often arrives at high velocity, especially from IoT devices, requiring robust ingestion mechanisms that can handle millions of events per second. Thirdly, the volume of data can be enormous and ever-growing, necessitating efficient storage techniques to manage petabytes of historical information. Fourthly, it often contains inherent patterns such as trends (long-term increase or decrease), seasonality (repeating patterns over fixed periods), and cyclical components (long-term, non-fixed patterns). Finally, time series data is often immutable once recorded, but new data points are constantly being appended, making it append-only in nature. These characteristics demand specialized approaches for storage, indexing, and query optimization that go beyond conventional relational database management systems, highlighting the need for advanced data warehousing methods.

While traditional enterprise data warehouses (EDWs) have served businesses well for decades, their underlying architectures and design principles are often ill-suited for the unique demands of modern time series data. Understanding these limitations is crucial for appreciating the necessity of specialized solutions.

Traditional data warehouses typically rely on relational database management systems (RDBMS) and star or snowflake schemas. These models are highly optimized for structured data, complex joins across multiple tables, and ad-hoc query capabilities over relatively static datasets. However, when confronted with time series data, several impediments arise:

These issues underscore why traditional approaches often fall short in providing efficient time series data storage optimization.

The sheer volume and velocity of time series data can quickly overwhelm traditional data warehousing architectures, leading to significant performance bottlenecks and scalability challenges:

These limitations highlight the urgent need for specialized data warehouse design for time series that can overcome these hurdles and provide scalable, high-performance solutions for modern big data time series architecture.

To effectively manage time series data, data warehousing strategies must evolve beyond traditional paradigms. Temporal data warehousing introduces specific principles to address the unique characteristics and challenges of time-varying information, ensuring both analytical power and operational efficiency.

At the heart of temporal data warehousing is the explicit recognition and modeling of time as a fundamental dimension. Unlike traditional data warehouses where time might be just another attribute, in temporal contexts, time often dictates data validity, transaction periods, and analysis windows. Two primary types of time are critical to understand:

Advanced temporal data warehouses often explicitly model both, allowing for complex queries that differentiate between when an event happened and when the system became aware of it. This distinction is vital for maintaining historical accuracy and supporting comprehensive time series analysis, especially when dealing with late-arriving data or data corrections.

Time series data often arrives at very fine granularities (e.g., milliseconds for sensor data, seconds for financial ticks). However, analytical queries might require data at different aggregation levels (e.g., hourly averages, daily sums, weekly medians). Efficiently managing these varying granularities and periodicities is a cornerstone of effective temporal data warehousing:

This approach allows analysts to query the most appropriate granularity for their needs without scanning massive raw datasets, improving query performance dramatically.

In a temporal data warehouse, ensuring consistent interpretation of time-related attributes across different fact tables is critical. This is achieved through conformed dimensions, particularly the Date and Time dimensions. A well-designed Date dimension table should contain attributes like year, quarter, month, day of week, day number in year, fiscal period, and flags for holidays or weekends. Similarly, a Time dimension can break down hours, minutes, and seconds. By linking all fact tables to these conformed Date and Time dimensions, analysts can:

The careful construction and use of conformed dimensions are fundamental to robust data warehouse design for time series, providing a consistent temporal context for all analytical endeavors.

The choice of data model is paramount for the efficiency and scalability of a time series data warehouse. While star schemas are a good starting point, specific adaptations and alternative models are necessary to handle the unique demands of temporal data.

For time series data, fact tables often contain a high volume of records, each associated with a specific timestamp. Several design patterns can optimize these fact tables:

An effective data warehouse design for time series often involves a combination of these fact table types, carefully chosen to reflect the nature of the data and the analytical requirements. For instance, an IoT data warehouse might have a detailed fact table for individual sensor readings (additive), and a snapshot fact table for device status (semi-additive).

Dimensions in a data warehouse represent the \"who, what, where, and how\" of the business. However, these attributes can change over time (e.g., a customer\'s address, a product\'s category, a sensor\'s location). Slowly Changing Dimensions (SCDs) are crucial for maintaining historical accuracy in dimension attributes, especially when performing time series analysis. There are several types of SCDs:

For temporal data warehousing, SCD Type 2 is often preferred as it provides a robust mechanism to track changes in dimension attributes over time, ensuring that historical facts are analyzed in the correct context. This is vital for accurate trend analysis and historical reporting.

Beyond traditional relational models, hybrid and NoSQL approaches are gaining traction for advanced data warehousing methods for time series. These offer flexibility and scalability that RDBMS often lack:

The following table summarizes a comparison of common data models and their suitability for time series data:

| Data Model Type | Description | Pros for Time Series | Cons for Time Series | Best Use Case Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Star/Snowflake Schema (RDBMS) | Normalized dimensions, denormalized fact tables. | Good for structured, moderate volume; familiar. | Poor scalability for high volume/velocity; slow range queries. | Financial reporting, small-scale IoT. |

| Time-Series Databases (TSDB) | Optimized for time-stamped data ingestion, storage, querying. | High ingestion rates, excellent compression, fast temporal queries. | Less flexible for complex joins with non-temporal data. | IoT sensor monitoring, real-time analytics. |

| Columnar Databases | Stores data column by column. | Efficient for analytical queries over few columns, good compression. | Writes can be slower; less suited for transactional workloads. | Clickstream analysis, large-scale metrics aggregation. |

| Data Lakehouse | Combines data lake flexibility with data warehouse structure. | Scalable storage, supports structured/unstructured, ACID properties. | Requires careful design and management; can be complex. | Unified platform for raw IoT, historical analysis, ML. |

With time series data often measured in terabytes or petabytes, efficient storage and rapid retrieval are critical. Time series data storage optimization involves a combination of smart compression, strategic partitioning, and specialized indexing.

For analytical workloads involving time series, columnar storage is often superior to row-oriented storage. In a columnar database, data for each column is stored contiguously. This offers several benefits:

Many modern data warehouses and TSDBs leverage columnar storage internally, making them ideal for advanced data warehousing methods for time series.

Partitioning and sharding are fundamental techniques for managing large time series datasets, improving both query performance and manageability:

Proper partitioning and sharding are critical components of data warehouse design for time series, directly impacting query speed, data lifecycle management, and system scalability.

While standard B-tree indexes are useful, specialized indexing strategies are required for optimal time series query performance:

The careful selection and implementation of these indexing techniques, combined with columnar storage and partitioning, form the backbone of robust time series data storage optimization, ensuring that analytical queries can be executed with minimal latency even on vast datasets.

The scale and real-time demands of modern time series data necessitate leveraging big data architectural patterns. These architectures are designed for high throughput, low latency, and massive scalability.

The data lakehouse architecture represents a significant evolution in big data time series architecture. It aims to combine the best features of data lakes (cost-effective storage, flexibility for diverse data types) and data warehouses (structured data, ACID transactions, schema enforcement, data governance). Key technologies enabling the data lakehouse include:

For time series, a data lakehouse can serve as the central repository for raw, high-resolution temporal data, enabling long-term storage at low cost. Processed and aggregated time series data can then be stored in optimized table formats within the lakehouse, making it readily available for SQL queries, BI tools, and machine learning models. This provides a unified platform for both batch and streaming analytics, simplifying the overall data ecosystem and supporting diverse advanced data warehousing methods.

Many time series applications, such as fraud detection, predictive maintenance, or real-time trading, require immediate insights from incoming data. This necessitates integrating stream processing capabilities into the big data time series architecture:

This integration allows organizations to perform near real-time time series analysis, making proactive decisions based on the freshest available data, while simultaneously persisting the raw data to the data lakehouse for deeper historical analysis.

To handle the massive scale of time series data processing, distributed computing frameworks are indispensable:

These frameworks provide the computational horsepower needed to transform, aggregate, and analyze vast quantities of time series data, whether for batch historical analysis or real-time insights, solidifying their role in robust advanced data warehousing methods.

The journey of time series data into a warehouse involves sophisticated ingestion and processing pipelines that can handle high velocity, volume, and variety while ensuring data quality and readiness for analysis.

Extract, Transform, Load (ETL) or Extract, Load, Transform (ELT) pipelines are the backbone of any data warehouse. For time series data, these pipelines require specific considerations:

Modern ETL/ELT tools, often leveraging distributed frameworks like Spark or Flink, are essential for managing these complex processes in a scalable big data time series architecture.

For transactional systems that produce time-sensitive data, Change Data Capture (CDC) and Event Sourcing offer powerful alternatives to traditional batch ETL:

Both CDC and event sourcing provide continuous, low-latency streams of data, enabling more up-to-date analytics and reducing the batch window for data freshness, which is crucial for modern time series analysis.

The success of any data warehousing initiative, particularly with the complexity of time series data, hinges on robust data governance and quality frameworks:

These governance practices ensure that the massive volumes of time series data are reliable, understandable, and fit for purpose, enabling accurate and trustworthy time series analysis.

Managing vast quantities of historical and real-time time series data within a data warehouse comes with significant responsibilities regarding security, governance, and regulatory compliance. These aspects are often as critical as performance and scalability.

Defining and enforcing robust data retention policies is crucial for managing storage costs, legal obligations, and performance. Not all time series data needs to be retained at its finest granularity indefinitely:

Effective time series data storage optimization extends beyond technical compression to strategic data lifecycle management, making it an integral part of advanced data warehousing methods.

Protecting sensitive time series data from unauthorized access is paramount. Granular access control and data masking techniques are essential:

These security measures are fundamental to maintaining trust and preventing data breaches within a big data time series architecture.

Many industries are subject to strict regulatory compliance mandates that impact how time series data is stored, processed, and retained. For example:

A well-designed temporal data warehousing solution must incorporate audit trails, data lineage capabilities, and robust security measures to demonstrate compliance. This includes the ability to retrieve specific historical data versions, prove data immutability, and manage data destruction according to regulations. Proactive planning for compliance is not an afterthought but a core component of data warehouse design for time series.

A traditional data warehouse primarily focuses on providing a snapshot of business operations at a given point in time, often overwriting historical attribute changes. A temporal data warehouse, on the other hand, explicitly models and tracks changes in data over time, preserving the full history of facts and dimension attributes (e.g., using Slowly Changing Dimensions Type 2). It\'s designed for analyzing how data has evolved, not just its current state.

TSDBs are purpose-built for time-stamped data. They offer superior ingestion rates, high compression ratios, and optimized query performance for temporal operations like range queries, aggregations over time windows, and interpolation. Unlike general-purpose databases, they are designed from the ground up to efficiently handle the unique characteristics of time series data, making them ideal for high-volume, high-velocity workloads.

Columnar storage stores data column by column, which is highly efficient for analytical queries where only a few columns (e.g., timestamp and a specific metric) are often retrieved over vast numbers of rows. This reduces I/O operations significantly. Additionally, data within a single column is often homogeneous, allowing for much higher compression ratios, saving storage space and further boosting query performance.

Data lakehouses provide a unified platform that combines the scalability and low cost of data lakes (for raw, high-resolution time series data) with the ACID transactions, schema enforcement, and data governance features of data warehouses. They allow for storing vast amounts of raw time series data, processing it with distributed engines like Spark, and then making structured, curated datasets available for analytics and machine learning, all within a single architecture.

Several strategies can be employed: 1) Use columnar storage and advanced compression techniques (e.g., delta encoding, Zstd). 2) Implement time-based partitioning to easily archive or delete older data. 3) Employ a tiered storage strategy, moving older or less frequently accessed data to cheaper storage tiers (e.g., cloud object storage with lifecycle policies). 4) Implement multi-granularity fact tables, retaining high-resolution data for shorter periods and aggregated data for longer durations.

The main challenges include handling extremely high write throughput (millions of events/second), ensuring data consistency and ordering, managing potential late-arriving or out-of-order data, accurate timestamp parsing and timezone handling, and performing real-time data quality checks. This typically requires leveraging highly scalable event streaming platforms (like Kafka) and distributed stream processing engines (like Flink or Spark Streaming).

The era of big data has unequivocally placed time series analysis at the forefront of data science, transforming how industries perceive and react to dynamic information. From the subtle shifts in climate patterns to the rapid oscillations of financial markets, the ability to accurately capture, store, and analyze time-indexed data is no longer a luxury but a strategic imperative. As we have explored, traditional data warehousing methods, while foundational, are often ill-equipped to handle the immense volume, velocity, and unique temporal characteristics of modern time series datasets. The journey towards sophisticated temporal data warehousing demands a paradigm shift, embracing advanced data warehousing methods that are specifically tailored for this domain.

The adoption of columnar storage, intelligent partitioning, specialized indexing, and the strategic integration of Time-Series Databases (TSDBs) are no longer niche considerations but essential components for time series data storage optimization. Furthermore, the evolution towards a big data time series architecture, leveraging data lakehouses, real-time stream processing, and distributed computing frameworks like Spark and Flink, provides the scalable and flexible foundation required to not only store but also extract actionable intelligence from continuous data streams. The intricate dance of efficient ETL/ELT pipelines, robust data governance, and stringent security measures ensures that these powerful architectures deliver trusted, compliant, and insightful analytics.

The future of data-driven decision-making is intrinsically linked to our mastery of time series data. Organizations that strategically invest in modernizing their data warehouse design for time series will unlock unprecedented capabilities in predictive analytics, anomaly detection, forecasting, and operational optimization. As technology continues to advance, we can anticipate even more sophisticated AI/ML integrations directly within these warehousing solutions, further blurring the lines between data storage and advanced analytical processing. The journey is continuous, but with the right architectural choices and a deep understanding of temporal data, businesses can transform fleeting moments into lasting insights, navigating the complexities of tomorrow with clarity and confidence.

Site Name: Hulul Academy for Student Services

Email: info@hululedu.com

Website: hululedu.com

مرحبًا بكم في hululedu.com، وجهتكم الأولى للتعلم الرقمي المبتكر. نحن منصة تعليمية تهدف إلى تمكين المتعلمين من جميع الأعمار من الوصول إلى محتوى تعليمي عالي الجودة، بطرق سهلة ومرنة، وبأسعار مناسبة. نوفر خدمات ودورات ومنتجات متميزة في مجالات متنوعة مثل: البرمجة، التصميم، اللغات، التطوير الذاتي،الأبحاث العلمية، مشاريع التخرج وغيرها الكثير . يعتمد منهجنا على الممارسات العملية والتطبيقية ليكون التعلم ليس فقط نظريًا بل عمليًا فعّالًا. رسالتنا هي بناء جسر بين المتعلم والطموح، بإلهام الشغف بالمعرفة وتقديم أدوات النجاح في سوق العمل الحديث.

ساعد الآخرين في اكتشاف هذا المحتوى القيم

استكشف المزيد من المحتوى المشابه

Master Time Series Analysis! Explore advanced big data processing methods for high-volume, real-time data. Learn scalable algorithms to transform your analytics.

Master Time Series Analysis! Explore advanced data warehousing methods, optimizing temporal data storage, design, and big data architectures for superior insights and efficient time series processing.

Unlock the power of data visualization for predictive modeling. Master effective techniques to interpret complex models, communicate insights visually, and transform your predictive analytics projects. Dive into advanced best practices and tools now!